Gay Community Services, Tucson activism in the AQA

by Jules Baldino, FOCAS intern, Fall 2024 / University of Arizona

“Indigenous notions of time consider the present to be structured entirely by our past and by our ancestors. There is no separation between past and present, meaning an alternative future is also determined by our understanding of our past. Our history is our future” – Nick Estes

1976 in Tucson, Arizona. A group of gays & lesbians met to organize a landline-based information hotline started as a project to help connect gay (and otherwise) people to social spaces, medical & health resources, religious spaces, restaurants, gay-friendly roommate connections, and more. One could call a phone number and be connected to a volunteer who could talk to them in real-time, letting them know about the gay landscape of Tucson, mapping out locations across the city that were friendly to gays, or that were explicitly established for gays. This list of establishments pulsed with life, carving out spaces in Tucson during the height of the Gay Liberation movement in the United States for gays & lesbians to connect.

They slipped typewriter printed lists with addresses and phone numbers into the plastic sleeves of photo albums and handed them out to volunteers as they manned the line. They used word of mouth information on the gay networks in town and information from Arizona Gay News, a newspaper published beginning in 1976, to include businesses and spaces that advertised their businesses as a part of their resource list. One could guess that even if these businesses were owned by gay people, expressing that they were explicitly queer-owned might not have been an option or a practice of the times. Posting ads in Arizona Gay News could serve as a code within the community.

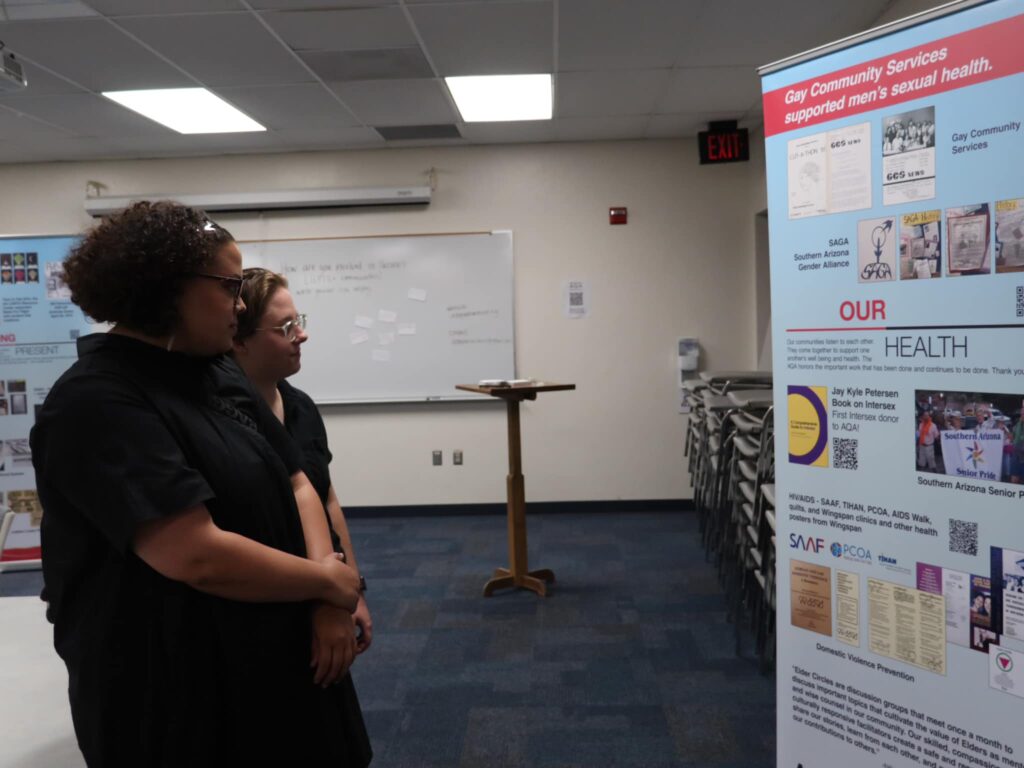

After a while, the organizing work of social connection led to community health work. The records show that GCS hosted a number of sexual health clinics, creating their own intake forms out of cut and paste text and photocopying them to pass out to attendees. The sexual health clinic worked with a local doctor to obtain medicine needed to treat common sexually transmitted infections, advocating for “a cure by the weekend” in a delightful celebration of queer sexuality amidst tending to community wellbeing. Gay Community Services cut a slice of a long legacy of queer community prevention and health work that had to exist outside of the medical industrial complex due to structural neglect and homophobia. Al Obermaier, one of the main organizers of GCS and the man who donated the GCS collection to the AQA, began responding to homophobic news channels that were incorrectly reporting on sexually transmitted infections through correspondence, beginning what would prove to be foundational dispelling of misinformation for the HIV/AIDS epidemic that would continue in the following years.

Through the archive, we can see how Gay Community Services developed their work into educating themselves on the HIV/AIDS crisis, attending national sexual health conferences to bring back information and prevention strategies, providing accurate information as it became available and as it changed over time. They organized to try and protect The Stables, the Tucson gay bathhouse, from being shut down amidst a national moral panic over bathhouses which targeted them as the sight of HIV/AIDS spread. GCS fought back, using a similar attempted case of a bathhouse shutdown in NYC to support how in actuality, similarly to many bathhouses across the country, The Stables was a localized site of prevention efforts, noting the number of condoms and informative pamphlets on the virus that had been distributed. While stories of HIV/AIDS advocacy and organizing out of major cities have become commonplace over the past few decades, it is rare to hear about the efforts of communities in a small town with less resources and a smaller queer population.

Community archives can be sites of power that hold a potential to connect a historical account of life with a present day fight towards connection and liberation. Archival collections inform us of our history, yes, but they also ask us to reflect on how we’re living now, where our ancestors worked to land us, and how that’s working out. Why are most of the sites from the Gay Community Services resource book now paved parking lots? Has liberation been on our minds and our hearts lately? Have we been wondering what life could look like outside of what we’re presently offered? Have we found each other amidst a hungry and quickly changing world? How have these been similar questions those who’ve come before us have also had to ask themselves?

Arizona Queer Archives is a community archive located in Tucson, Arizona, 60 miles from the US – Mexico border. AQA’s goal is to connect queer and trans people in Arizona with each other through archival collections of materials and mementos kept and cultivated, signs of life and struggle. In a state known for being socially conservative, known for its violent state-backed border policies and crumbling educational infrastructure, the queer archives stand out as a presence of queer desire and life, in all of its mess and glory, its fervor and its failures. The Gay Community Services collection locates inspiration for the continued fight queer people have for a life of dignity and freedom. The fight continues, and with our ancestors at our backs and evidence of the work here in our collections, we can continue to orient and demand life for all of us.