Website: https://thedunbartucson.org/

IG: @thedunbarpavilion

Dunbar History:

Before 1909, Arizona schools were not segregated. In 1909, the Arizona legislature passed a law mandating that Arizona’s African-American school children be segregated from the other races for their first 8 years of school. When Arizona became a state in 1912, they changed the wording of the law from “mandatory” segregation to “permissible to segregate.”

The Tucson School District chose to follow the practice of segregated schooling by creating a Colored School. The Colored School’s Principal was Mr. Cicero Simmons, a graduate of Tuskegee, who also taught all the classes. The school was held in a vacant building at 215 E. Sixth Street. African American families protested the segregation of their children into this inadequate facility by boycotting the school. The boycott lasted only two weeks before broken—and as the year progressed, the school grew to 11 students.

In 1918, the school moved to a 2-room brick structure at 325 West Second Street (its present location) and became the Paul Lawrence Dunbar School—after the internationally recognized Black poet and author—at the insistence of the Black community. Once the Dunbar school opened it became a focal point for community activities. With the help of dedicated teachers and concerned parents, the children at Dunbar school managed to receive an excellent education despite the poor facilities and lack of resources. Dunbar had no auditorium, no real library, no cafeteria, and no gymnasium, and the class books were used and handed down from other schools. Despite these inadequacies, there was an atmosphere of unity and togetherness with African American teachers who were deeply motivated to teach beyond scarcity and expectations.

Prior to 1920, students graduating from Dunbar who wanted to continue their education were forced to teach each other in the old Roskruge School (501 E. 6Th Street) after classes for other students were done for the day. In the 1920s, this practice changed and students were allowed to attend Tucson High School. While, at that time, the school contained students of all races, Black students had separate homerooms and there were restrictions on their participating in many school activities.

In 1951, the Tucson schools voluntarily agreed to dismantle the segregated school system. Dunbar school was integrated in 1952 (although this remained in dispute even through 2024) and was renamed John Spring Junior High School, after one of the first caucasian teachers in Arizona, when it was a territory.

DUNBAR SCHOOL SONG

Hail to Dunbar Junior High

A grand old school is she

Happy boys and girls all

Pledge their loyalty to thee

We will try to bring her renown

Never shall her banner go down

So hail, hail to to Dunbar High

Her glory shall never die

Dunbar Mission:

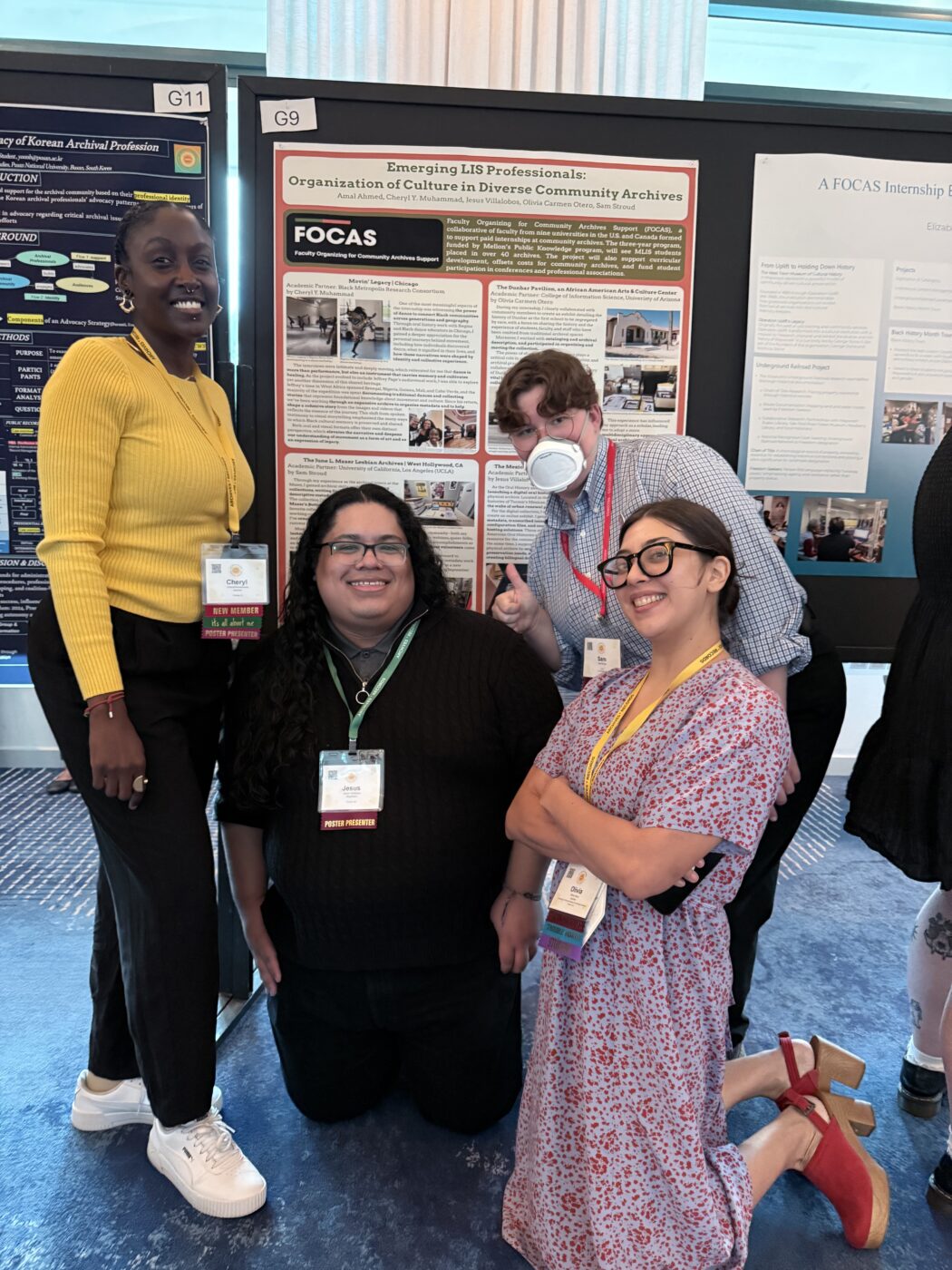

The mission of Dunbar Pavilion is “to honor the past, celebrate today and shape the future of the African-American community”. The vision for the center is “Striving to ‘Be the Best’ African American culture center in America”. The goals of the Coalition are to convert the campus into a space that 1) will exhibit the contributions of African-Americans to the development of Southern Arizona, and 2) anchor and house programs and organizations that support education, arts, social justice, health, economic well-being, and civic engagement reversing the effects of segregation throughout the region. The Dunbar’s collections aim to reflect the mission of the organization.

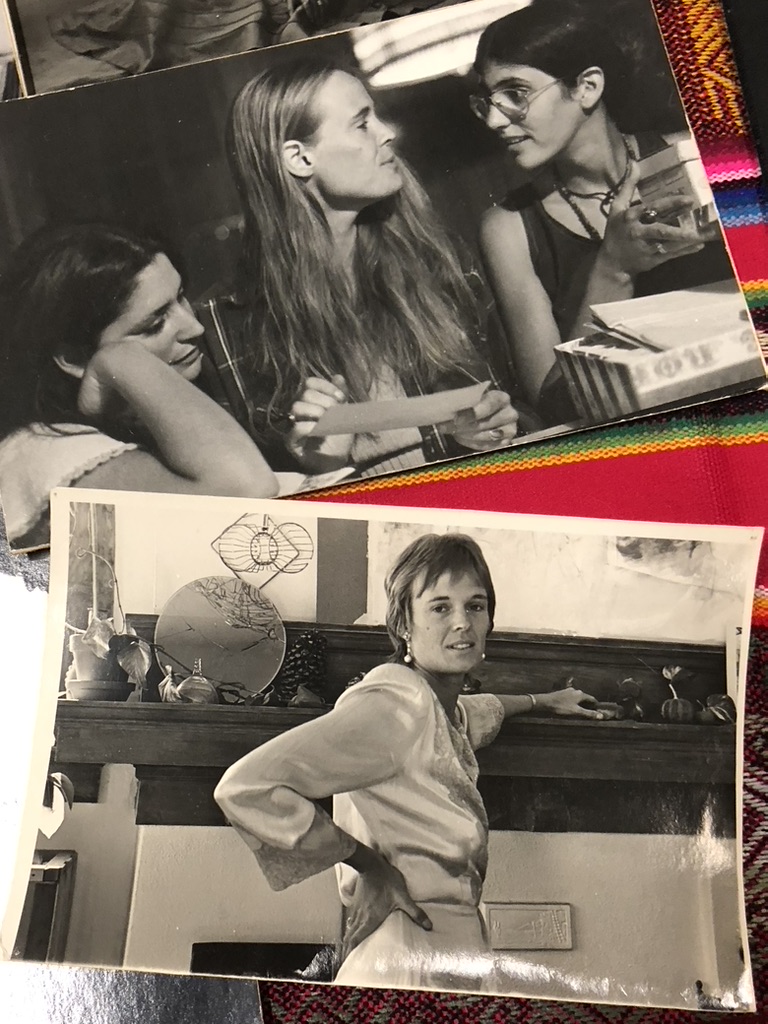

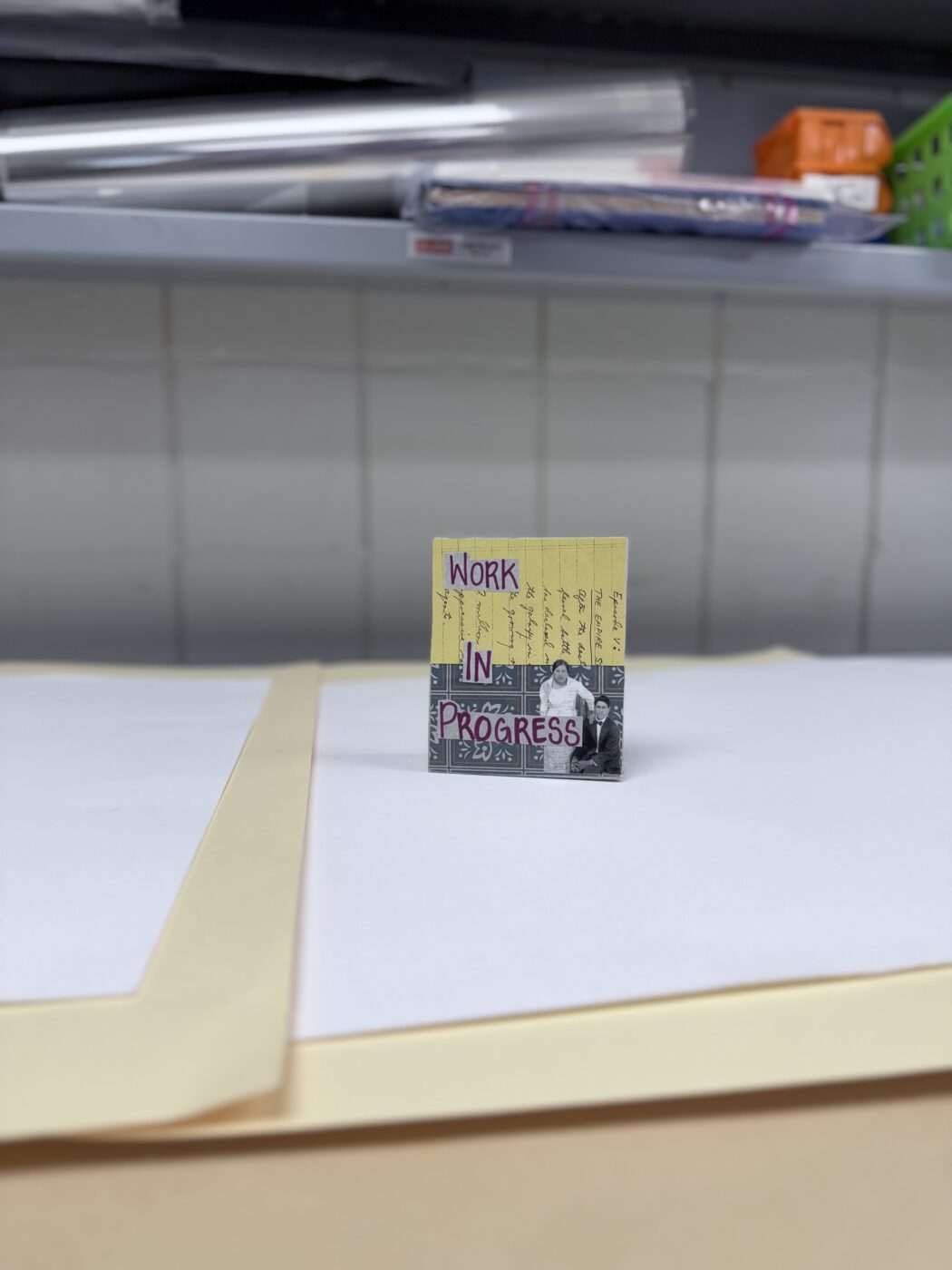

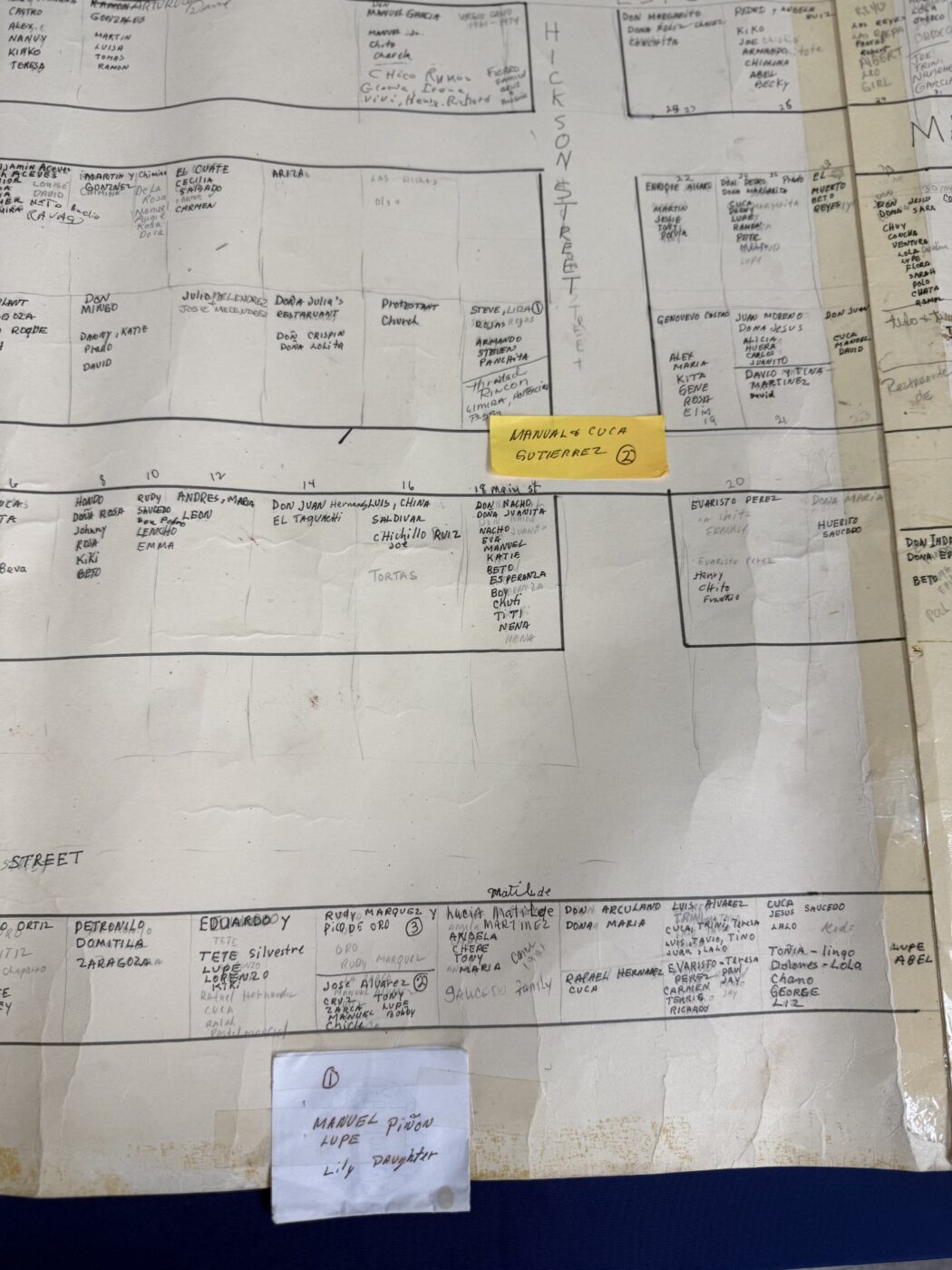

Collections Include:

The collections held by the Dunbar include archival materials in print, analog, and digital formats, and material artifacts. Items include art, oral histories, photographs, books, vinyl, broadsides, furniture, textiles, and archival documents representing the history of Dunbar and the African-American community in Tucson and the greater Southwest. Collections items have been acquired from alumni of the Dunbar School, Tucson residents, and others who are interested in the preservation of the school and community history. Materials are collected as part of the effort to develop an archive, permanent and temporary exhibits, and varied public programming. The Dunbar’s designation and preservation as an historic site itself will also enable visitors to experience the stories told in its exhibits and archives within context.