By Nicole Hayes, FOCAS Intern, Spring 2025 / University of Arizona

I spent the past semester as an intern at the Arizona Queer Archives—a community archive based in Tucson, Arizona that collects and preserves histories pertaining to queer communities across the state. Quite naturally, as a geographically-specific archive focused on a specific marginalized community, many of the collections overlap—but also diverge—in interesting and meaningful ways.

Throughout the semester I processed a collection, hosted open hours, and collaborated with colleagues to create two exhibitions. This gave me the opportunity to apply abstract theoretical archival concepts in a more tangible way, while also giving me the space to consider how the more the technical, skill-based side of archival work applies within the context of community archives. As an intern, I had a great deal of autonomy which was simultaneously freeing and yet carried a weight of responsibility. The first couple of weeks I spent a lot of time just exploring different collections with the hope of developing a focus. Because of the flexible nature of community archives, different interns and volunteers take different approaches to processing. I spent days inventorying a collection that I thought was partially processed only to discover that it had already been processed in full. While my involvement with this particular collection shifted, it was still a valuable way to familiarize myself with the collections of the AQA. The time I had dedicated to many of the collections later became useful in gathering materials for an exhibition and movie night that we hosted at the LGBTQIA+ Institute, where the AQA currently resides.

An exhibition featuring curated kink and leather materials from the archives

The collection I ended up working on for the majority of the semester was Curt Stubb’s collection. Curt was a poet, writer, and docent at the University of Arizona poetry center who had lived in Tucson for over three decades. He wrote a column called “A Remarkable People” for the Tucson Weekly Observer—a seminal but now defunct gay newspaper published in the late 80s, 90s, and aughts. I began with an inventory of everything within the collection by taking detailed notes of what I found—trying to figure out where everything fit. Curt’s collection consists of his written work, personal documents, science fiction memorabilia, queer zines, play programs, and publications relating to gay history.

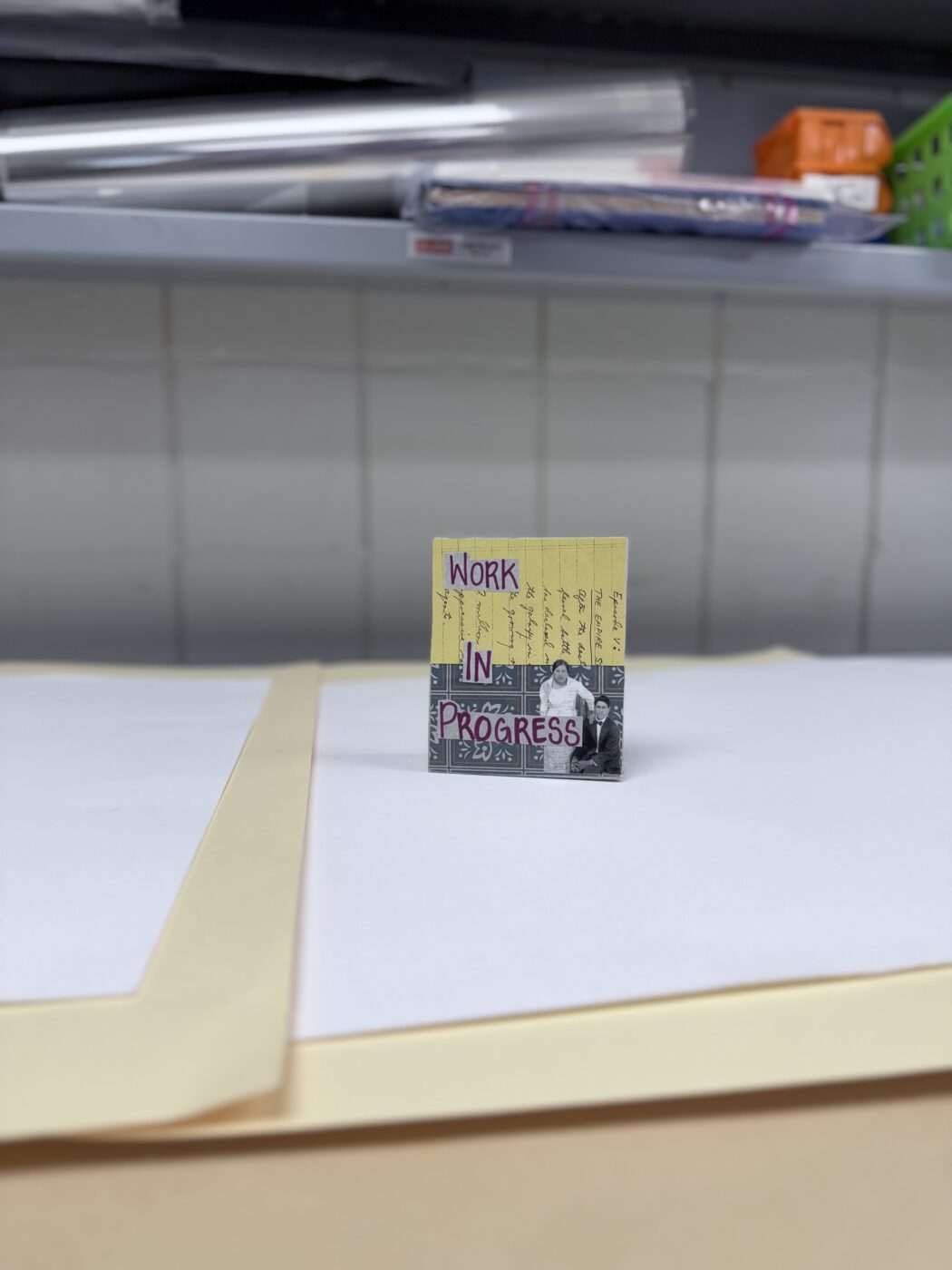

Album with rat damage containing clippings from Curt’s column in the Observer

One of the first things that struck me in Curt’s collection was a green folder with “Will” written on the front. Inside was a hand typed will and testament, signed by a notary. Included with the will is a record of his birth, power of attorney forms dated a year prior to his death, and a transaction form for the intake of his three cats. The first directive on his will gives information on the shelter he wanted his cats to go to, along with the entirety of his savings. Following this folder, there are medical records, final bank statements closing out his accounts, his death certificate, amongst other vital records. Despite never knowing Curt, I cried the first time I read over these records. It was not the first thing I had looked at in his collection, but it is the first thing I recall. I thought about these documents all semester long—how they fit into his broader collection, and what vital records such as birth certificates, living wills, and medical records provide evidence to. I contemplated the affective value of these records and how they interacted with the rest of the collection. While I had become emotional looking at them, they also felt very clinical compared to the other records—which include a cigar box of photos, jewelry, and other mementos. It was these more clinical, almost administrative records that frustrated me, and at the same time laid a path forward for how I arranged the rest of the collection. On my way home from the Archives one day, I found myself contemplating how reductive these administrative records can feel in the grand scheme of things. They say so little about us yet dictate so much of our lives. Curt’s collection spans his life: 1948-2019, beginning with his birth certificate. These snap shots tell us very little when separate from one another—engendering snap shots that seem to regard living and dying as singular events rather than a process. Conversely, I wanted to organize the records in a way that faithfully reflected the complexity of Curt’s life, and his own connection to the communities with which he belonged.

So, I led with Curt’s work—his poems and short stories which hold space for different facets of who he was. The rest of the series that followed the arrangement process shed light on Curt’s connection to the different communities he belonged to and additional context for the roles he occupied in these spaces. Curt obtained his BA in Creative Writing and took library classes—part of his collection works to document gay histories through newspaper articles and other publications, which he refers to as his gay archive in his will. The administrative records, often called vital records, in context to the rest of the collection, reflect Curt’s values, his relationships, and the importance of the connections he held with others throughout the course of his life. In contrast, I couldn’t help thinking about how often vital records and legal documents are weaponized against marginalized communities.

When creating a finding aid, I often had to examine materials closely for context, as searches elsewhere provided few clues. At times, the only information I would find would be other community archives—for example at one point I found two projects aimed at documenting queer zines. One day while searching play programs, I discovered ads for businesses referenced in another collection which a fellow intern organized an exhibit around. When sharing this with a colleague, they got excited seeing the name of the theatre and asked if there was more. I told them there was an entire folder—they squealed with excitement and showed me another box which contained more materials from the theatre: a t-shirt, posters, another play program. Neither of us had been able to find any information about the theatre online, but these two collections together filled a gap. The archive itself had become a site of research for history that often gets buried. During the aforementioned exhibit, based around a collection of records pertaining to grass roots organizing, a patron asked, “this was happening in the 70’s?!” The devaluing of these records results in erasure. The work being done at the AQA and in other community archives is important in preserving these lost histories—but bringing communities into the archives (or bringing the archives to them) is equally as important.

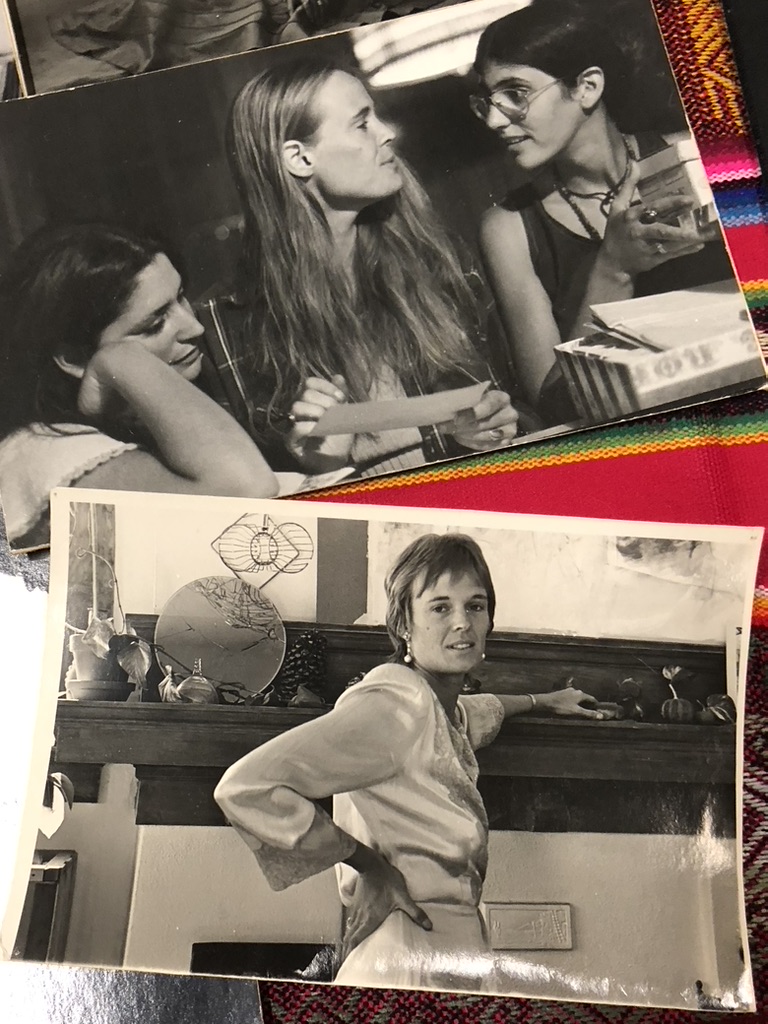

Copies of One in Ten Theatre programs from Curt’s collection alongside one in ten materials from the Southwest Feminist collection